.png.transform/rendition-xs/image_image%20(1).png)

The Many Meanings of Malvasía from Spain

Malvasía is a familiar grape name to many a wine drinker, yet one that escapes easy definition. We’ll crisscross Spain to have a closer look at the different expressions of this ubiquitous grape.

To be fair, according Wine Grapes by Jancis Robinson MW and José Vouillamoz, “Malvasia” is a generic name given to a wide array of grape varieties around the world, forming part of a name or synonym in roughly 70 different cases. Many of these are completely unrelated to each other, with skin colors that range from grey to pink and from black to white.

Italy and Portugal are the Malvasía kings, both with around 13,000 hectares planted. Of Spain’s roughly 4,000 hectares, over half are found in the Canary Islands, with the rest scattered throughout Catalunya, La Rioja, Castile-Leon and Galicia. Wine styles range from still to sparkling to fortified and from dry to sweet. Further confusion comes from the litany of names under which the grapes are planted, as we’ll see below.

Without a simple connection to unite them all, we’ll crisscross the country to have a closer look at the different expressions of this ubiquitous grape.

Malvasía fron the Canary Islands

In the Canary Islands Malvasía finds two main expressions, Malvasía de Lanzarote (aka Malvasía Volcánica) and the genetically distinct Malvasía Aromática (aka Malvasía de la Palma and Malvasía de Tenerife). It’s interesting to note that Malvasía de Lanzarote is actually an offspring of Malvasía Aromática, although slightly less aromatic.

While the islands’ subtropical climate might not seem ideal for viticulture, vines benefit from a strong cooling influence via the potent north-east Alisios winds. This, combined with the earliest grape harvest in the northern hemisphere, has allowed wineries like El Grifo in Lanzarote, which dates to 1775 no less, to harvest fully ripe grapes while retaining high acidity levels, bringing greater freshness and balance to the final wine. While this is a crucial factor for any wine, it’s especially true for one as intense and rich as their Malvasía Canari, a recreation of the famous fortified Canary Sack wines from the 17th century.

While not exactly a solera (link to ABC’s of Sherry article), Malvasía Canari is produced every 4 to 5 years in order to refresh the winery’s stocks, with the goal of achieving an average age of at least 30 years in casks before bottling. The current release is a blend of three specific vintages: 1956, 1979 and 1997.

Following harvest, the grapes are partially dried for about a week, during which water evaporates, thus concentrating the pulp’s sugar and acid levels. This rich grape must is then partially fermented until the sugar levels decrease to roughly 90 g/l, at which point neutral grape spirit is added to kill off the yeast, leaving behind a naturally sweet wine with around 17% abv and at least 7g/l of total acidity. The raisination of the grapes, along with the long oxidative ageing produces a wine that is deep amber in color with flavors of nuts, candied orange peel, honey, vanilla and cedar.

Malvasía from the Spanish mainland

Outside the Canary Islands, the dominance of Malvasia Aromática and Malvasía Volcánica declines, giving way to Malvasía Castellana, an overarching term with multiple synonyms that include Doña Blanca, Malvasía Blanca, Alarije, Malvasía Riojana, Blanca Roja, Rojal and Subirat Parent.

Compared to its Canary Islands’ counterparts, Malvasía Castellana has lower acidity and is much less aromatic. Its wines are more defined by their unctuous, silky texture with added complexity often attained via barrel fermentation, MLF, and/or ageing on fine lees, techniques also applied to one of Malvasía’s classic partners, Rioja’s own Viura.

Malvasía from Rioja

It is in fact within Rioja that Malvasía formed part of the region’s traditional red and white blends, interplanted among other varieties in the mixed vineyards of past times. Today it represents just 2% of the region’s plantings, surpassed even by foreigners such as Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc.

With so few hectares, the lack of varietal examples in the market is no surprise, although two worth highlighting come from Abel Mendoza and Bryan MacRobert respectively.

Both producers cite the importance of older vines and cooler mesoclimates to achieve physiological ripeness (i.e. flavor development) without losing Malvasía Riojana’s delicate sugar/acid balance. They also alluded to the grape’s more oxidative nature, which can quickly take on bottle-age tertiary notes of baked apple, quince paste, dried orange peel, straw, and honey.

For their part, Abel Mendoza and his wife Maite Fernández use barrel fermentation and lees ageing to bring added breadth, character and structure to their wines. While new barrels are used, their wines are anything but oaky, and the wood’s additional tannic structure helps stabilize the wine, bringing muscle without weight.

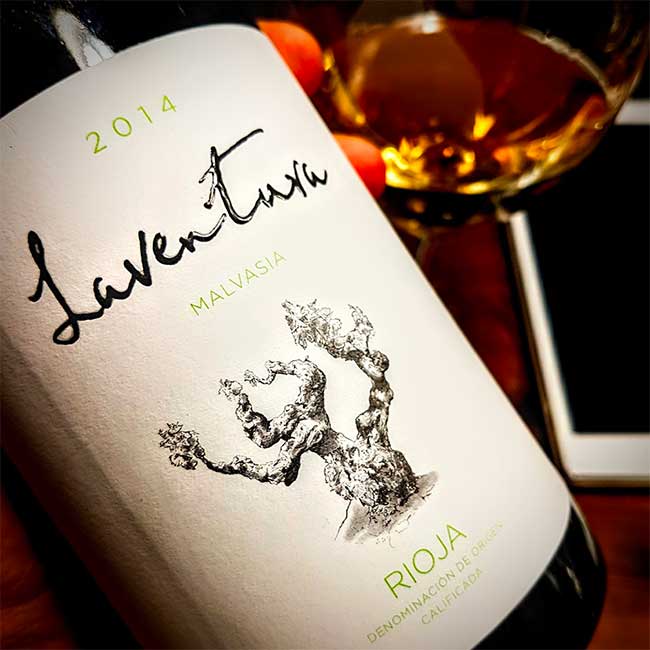

MacRobert on the other hand, under his label Laventura, produces a textural lees-driven Malvasía derived from a brief period of skin-contact during fermentation to extract additional aromatic compounds, followed by a year on fine lees in an unlined cement egg, in search of the controlled micro-oxygenation provided by wood without the associated flavors.

Malvasía from Catalonia

In the north-east corner of Cataluña, Malvasía Aromática takes precedence once again under the local synonym Malvasía de Sitges. As a grape that ripens much later than its eponymous cousins, Malvasía de Sitges builds up sugars more slowly, thus retaining more acidity while the aromatic compounds have time to develop.

Therein lies the initial motivation behind Freixenet’s medium-sweet Malvasía Cava, launched in 1991 and only made in 2001, 2009, and the current release, 2011. Marta Raventós explained that the base wine, which undergoes the second fermentation in bottle is 100% Malvasía de Sitges, while the licor de expedición is a blend of Malvasía grape must (which provides the sweetness) and a dry still wine made from the traditional Cava varieties of Macabeo, Xarel·lo and Parellada. The still wine has been aged in chestnut casks for more than 20 years, adding a noticeable but integrated note of evolution to the final wine, with flavors of honey, raisins, dried apricots, and nuts, all of which is reinforced by the 8 years of bottle age before release.

So the next time you see the word “Malvasía” on a wine label, remember that you can never judge a book by its cover.

Text: Nygil Murrel.