.png.transform/rendition-xs/image_image%20(1).png)

Spain’s Most Exclusive Olive Oil Comes From Millennia-Old Trees

by Benjamin Kemper

by Benjamin Kemper

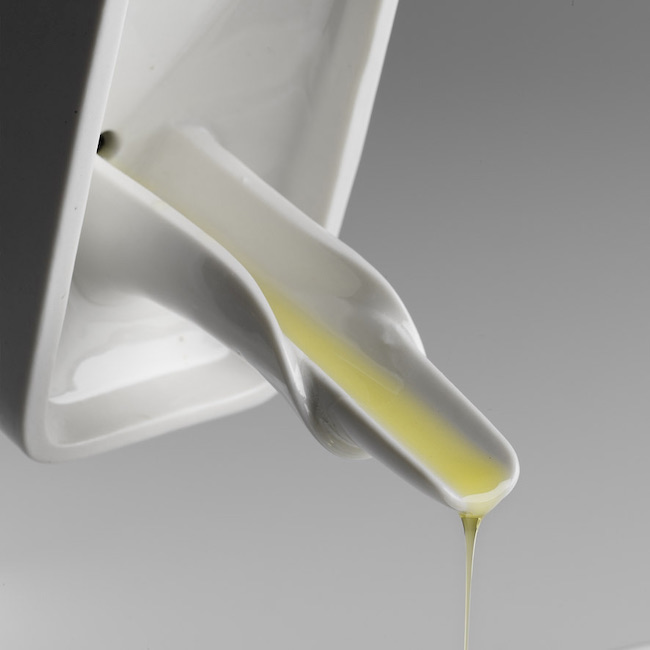

The thick, golden liquid dribbles out a tiny porcelain spout onto a slice of sourdough bread. It collects in yellow-green pools that glint in the sunlight. This is heady stuff: Aromas of lemon zest, almonds, and freshly cut grass transport you to the Mediterranean as your teeth crunch through the crust. Then, a velvety and enveloping creaminess as you crunch, followed by a throat-catching kick that makes your eyes water, a sign of the oil’s utmost purity.

This is what it’s like to taste El Mil del Poaig. A sensory thrill on par with fine wine, the Spanish extra-virgin olive oil has a complex nose and a finish that lingers long after you’ve swallowed. But beyond its technical achievements—the oil is beloved by big-name chefs and is one of the world’s 20 best olive oils, according to the Flos Olei awards—El Poaig also has a fascinating story to tell, one that sparks the imagination as well as the salivary glands.

The olive trees used in the production of El Poaig are 1,000 to 2,800 years old. Registered and protected by the Spanish government as árboles monumentales (monumental trees), their immense trunks and gnarled branches are a hallmark of the landscape of El Maestrat, a rugged mountain region straddling Catalonia and Valencia that has the highest concentration of millenary olive trees on earth.

Some of El Maestrat’s olive trees have been bearing fruit since before Roman times, but by the early 2000s, their future was in jeopardy. “The trees were being sold off left and right to decorate palaces in France and the like,” said Joaquim Solano, co-founder of El Poaig along with Manuel Arnau. “We thought, that’s a problem. They were uprooting an integral part of the region’s heritage along with the trees.”

It dawned on them: What if they could ensure the trees’ survival by turning their fruit into high-end olive oil? Solano and Arnau knew that farga olives (the main variety harvested from millenary trees) produced exquisite oil, but making oil solely from the fruit of these ancient specimens presented a litany of problems. For starters, old trees generate so few olives that they must be harvested by hand. To make matters worse, thousand-year-old olive trees don’t come in well-delineated groves in El Maestrat—they’re strewn willy-nilly across the vast, rugged terrain; to access them, Solano and Arnau would need to go door to door requesting permission from dozens of farmers.

But tree by tree, farmer by farmer, the duo were ultimately successful. “Locals saw that our project was solid and that El Maestrat would finally have an image it could be proud of,” said Solano. When El Poiag was founded in 2008, Spanish newspapers called it the most expensive oil in the world. TIME featured it as one of the 100 best inventions of the year. The price is €160 for a 500ml bottle, plus shipping. Yes, today there may be pricier oils on the market, as well as a handful of other producers making oil from millenary trees, but El Poaig continues to be a pioneer in the category of luxury oils. “There are super-expensive olive oils on the market that put diamonds on the bottles, but that’s not us,” said Solano. “We think the most valuable thing should be what’s within.”

It didn’t take long for the food world to go loco over Spain’s new liquid gold. José Carlos Capel, the restaurant critic of El País, Spain’s leading newspaper, called El Poaig “exceptional”. The oil began cropping up on Michelin-starred menus from Tokyo to Hong Kong to Madrid, where Michelin-starred chef Mario Sandoval used it in the world’s most expensive tortilla española (Spanish potato omelet), made with La Bonnotte potatoes, Añana salt, and acorn-fed chicken eggs. Each omelet serving four cost €837 to make. But El Poaig’s loudest advocate, perhaps, is celebrity chef Quique Dacosta, who serves each guest at his three-Michelin-star restaurant a bread course centered on a generous glug of the oil.

Such an exclusive product—a scant 2,000 bottles of El Poaig are produced each year—demands a container up to its standard. Enter CuldeSac, a Valencian design firm that caters to the likes of Hermès, LVMH, and Aston Martin. Tasked with manufacturing a dispenser that would pour beautifully and keep the oil fresh while inspiring ooh and aahs, they settled on a heavy porcelain bottle with a distinctive, tongue-like spout. Solano explained that porcelain’s opacity protects the oil from the light, while its insulating qualities keep the liquid at a more stable temperature than the usual glass or metal. Each ceramic bottle is made by hand.

By now you may be wondering, how on earth does one cook with such a rare and distinctive oil? The short answer is, you don’t. According to Solano, El Poaig is best as a finishing oil, one you drizzle over, say, fat slices of in-season tomatoes, fresh sourdough bread, or perhaps a wedge of bittersweet chocolate cake along with a flick of crunchy salt.

Solano says there’s no such thing as “best” when it comes to olive oil and makes no such claim of his own. Taste, after all, is subjective. But when you consider El Poaig’s (literally) deep-rooted history, painstaking production, and one-of-a-kind package, it’s clear that this oil is one of the most precious foodstuffs on the planet. “There are many great oils out there, but imitating El Poaig is impossible,” Solano said.