.png.transform/rendition-xs/image_image%20(1).png)

Fernando Mora, Master of Wine: "A Revolution is Unfolding in Spain"

The Spanish Master of Wine talks about the role that unique high-quality wines can play in raising awareness and the value of Brand Spain

A weekend of wine tourism in La Rioja led this city-dwelling mechanical engineer – who was happy in his job – to make a radical life change.

Fernando Mora fell head over heels in love with wine while visiting the Vivanco Museum of Wine Culture. His inquisitive nature and his friendship with Mario López, whose family had vineyards, resulted in Fernando making his first hundred litres of wine a few months later, in 2008, in the bathtub of his apartment. Today, Bodegas Frontonio, the winemaking project he founded with Mario López, is one of the great examples of the wine revolution in Spain, with quality and identity as its hallmarks.

Bodegas Frontonio not only makes some of the most reputable Grenache wines in the world, but has also helped the village of Alpartir (Zaragoza) – with a population of four hundred – to revive its historic vineyards, make a name for itself in the world of wine and provide a livelihood for locals wishing to remain there. Along the way, this energetic enthusiast worked towards his Master of Wine degree, accomplishing it in a record time of two years and nine months His thesis speaks to his ability to question the status quo: a new type of classification for wines in Spain based on the quality of the vineyards and not on how long wines are aged.

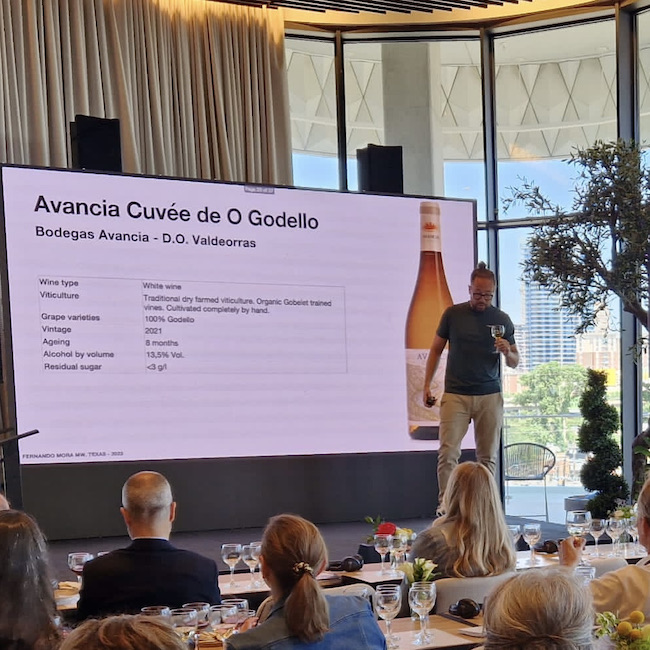

Fernando Mora is part of the distinguished delegation of Spanish product ambassadors who are currently touring the state of Texas – with Spain Fusion Foods and Wines from Spain – to open up the American market. In this interview, he talks about the role that unique high-quality wines can play in raising awareness and the value of Brand Spain.

During his talk at Spain Fusión Texas he spoke about the great diversity of Spain’s territories and wines. What opportunities do these wines from little-known areas, that are singular or with small productions, have in a market like that of the United States?

“We tend to talk about the world of wine as if it were something unique, when there are, in fact, a lot of different mini-worlds. When it comes to the commercial world, it has very little in common with small-production speciality wines, except that they are all part of Brand Spain, which is what unifies things. Because the kinds of vineyards, the way wines are made and sold, or the reasons that lead a customer to consume one type of wine or another have little to do with each other. For me, these small-production, special higher-priced wines contribute to positioning the brand. And if, thanks to a few very good wines sold to the right people, Brand Spain grows in esteem, commercial wines will also sell at slightly higher prices, as is the case in France. And, more importantly, growers will be paid more for their grapes.

Is there a market for these wines in the United States?

“I’ve been selling in the United States for a decade and I’ve seen a remarkable evolution. In the past, it was just ‘value for money’. A very clear example is that people weren’t willing to pay the same for a Spanish wine as they would for a French one, but now it’s a different story. Nowadays, people are discovering that Spain can make great wines at a high but reasonable price in relation to its competitors in other countries, and that’s good, because it helps to position Spain as a brand of quality wines; not as the world’s source of bulk wine or as a producer of good but inexpensive wines. Spain can produce great wines at a reasonable price in areas that were previously unknown, and the United States is a very receptive market. It’s not a very mature market where buyers tend to be reluctant to change. Americans love new things if they’re good. That’s why it’s working so well for us and that’s why we’re all here to sell.”

Spain is still the world’s leading bulk wine producer. How sustainable is that?

“Well, when it comes to selling inexpensive wine, Spain is, by and large, the country in the world that sells the most. If you sell in bulk but you sell well, fine, but the problem is that we only know how to sell at price, and if you sell at price, you sell when you lower prices to where others don’t want to go. Of course, if you have a massive vineyard and can’t sell at value, your priority is to get rid of everything so the following year you have room for the grapes again. You avoid a disaster and then start over. But things are the other way around: I believe that I’m able to make a specific wine, and because of its quality and because of what I know about other wines around the world, I know my wine is worth that much so I’ll defend it tooth and nail. It’s the only way for my area, Aragón, to be respected as a producer of Grenache wines. If we focus on price, people will only think that we are cheap, so they have to know that we have some of the best Grenache wines in the world. And if we don’t have them yet, we have to make them, and in order to make them we have to sell well to climb the ladder, which won’t happen overnight. It’s not a question of ‘no, I’m a commercial winery but now I make a very expensive wine to promote myself.’ That’s unrealistic.”

Is your path an example?

“I started off making a delicious commercial wine called Botijo Rojo, which worked really well within its price range. Thanks to that wine, I was able to go up a level, then another, then another, until I made El Jardín de las Iguales; it took me ages, with different vineyards and a sizeable investment. What you can’t do is fool people as they aren’t stupid. You go crazy just to sell a bottle of wine. You have to find the right vineyard, do a great job growing the grapes, harvesting them at the perfect moment, make the wine properly, age and bottle it... And then, you have to give clients a million reasons why they should buy your wine and promote it, because if not, you’re not going to be able to sell the next year’s vintage. It’s a very complex equation. Selling wine is complicated because it’s intangible, because it’s a liquid and you have to explain how it differs from other liquids of the same colour.”

A revolution is unfolding in Spain. Wine is being produced in the most surprising places and varieties are being revived, but a lot of vines are also being uprooted because the grapes don’t sell.

“No farmer likes to pull up the vines that their father or grandfather planted. They do it because they can’t afford to sell their grapes at prices that don’t cover costs. As we’re not able to transfer the value of those grapes into a wine and explain that wine to consumers, they’re not willing to pay for the magic that’s in the bottle, so they pull up the vines and everything goes out the window. The mosaic of old vineyards we had in Spain was our heritage. It’s a lovely thing to say. People talk a lot about old vineyards but then they don’t cut the mustard.

My life has been to buy the few old vines left in my area and enhance their value, but when nobody had faith in that, I had to defend it. Time has now proved me right, but very often we almost didn’t make it.”

What’s your personal story regarding the world of wine?

“I’m actually a mechanical engineer. I was taken to see the Vivanco winery, which has the most beautiful wine museum in the world, and I realized that there was definitely something about wine for it to have been sung about, written about and painted for so many years. And there was the technical side which, as an engineer, interested me a great deal. Then there was the wine tasting aspect, which fascinated me, because you’re trying to classify something that’s very tough to classify. All that led me to begin making wine in my apartment.”

In your apartment?

“Yes, I made a hundred litres, and from then on, I wanted to learn more. It was on that journey that I met Mario López, my business partner. Next, I started studying to be a Master of Wine, and, by going to the best wineries in the world, I realized that the vineyards in my area had nothing to be ashamed of when compared to numerous wineries producing very good reputable wines. So, we said: let’s learn what our journey is. Let’s travel around the world, taste wines in many places, work at other wineries and then bring all that knowledge back home, because if we only copy from the guy next door, we’ll end up with the same results. We’ve got to be disruptive, rethink everything, study how wines were made a hundred years ago and ask: What aspects about how wine was made a century ago interest us? This and this. And what do we know today that they didn’t know back then? Well, this and this. We must cast our eyes to the past in order to look to the future in a different way.”

He speaks of returning to the land. For many years, wine was made in a winery and the protagonist was the winemaker or cellar master.

“Yes, and no one was interested in the winegrower.”

But now, importance is starting to be given to the winegrower, but it’s hard to pass the baton on to the next generation.

“In Aragón, we are that generation. We’ve been able to buy the vineyards we’ve bought because the person who took care of them couldn’t do so any longer. It’s lovely to enjoy a glass of wine in a restaurant, but if we’re not in the countryside and we don’t take care of those very special vineyards, our wines won’t be what they should be. Moreover, wine anchors the locals to the land. We came to this village called Alpartir, where viticulture had been the cornerstone of life to the point that the older generation still get excited when they talk about it, but production declined and the only thing left was to make wine for their own consumption. The vineyards we took on were used only for that. As it so happened, they were good ones. I mean, if you’re going to leave something to make wine for yourself, you only keep the best. And then we thought: since we’ve found these vineyards here, we’re going to look for a winery to make wine in the village, and we’re going to work with the four hundred or so locals. It is like closing the circle. To keep people from leaving, you’ve got to take care of the forest in times when it’s burning.”

Are you able to find knowledgeable young people willing to work in the vineyards?

“People here have always worked the land. They have to be taught some things, but I’ve also learned from them. They’ve taught me many things I didn’t know about the land and also many values, because villages, which are less developed in some ways, are much more evolved when it comes to sharing, caring for your neighbours, working together... I decided to move to the countryside. I live at the winery itself, something that’s not very common here in Spain, but for a French vigneron, the winery is their home. When you become so connected to a village, with the vineyards, with your wines, with the people who work with you – who are your family – that’s when everything really comes together and you can raise things to a new level.”

How does being a winemaker go hand in hand with being a Master of Wine?

“I’m extremely proud to be Master of Wine. I decided I wanted to become one and I was lucky enough to be able to achieve it, but my life goal wasn’t to be Master of Wine; it was to make one of the best Grenaches in the world, or at least attempt it. As I started studying at the same time as I was getting my winery off the ground, having to taste a lot of wines helped me gain more insight into what kind of wine I wanted to make. I visited many, many wineries and that helped me implement many things in mine. Then, of course, achieving it helped encourage people to try the wines I make. Being a Master of Wine opens doors, but those doors only stay open for two minutes. If the wine’s not good, they close again.”