.png.transform/rendition-xs/image_image%20(1).png)

Asturias, the Awesome Land of the 300 Cheeses

Susan Sherril Axelrod, editor-in-chief of Culture: the word on cheese magazine and Culture Media, explores the largest cheesemaking region in Europe.

At the International Cheese Festival in Oviedo this November, a display of Asturian cheeses on the mezzanine of the Palacio de Exposiciones y Congresos stretched nearly as far as the eye could see. In between my judging duties for the 2021 World Cheese Awards (WCA), held in conjunction with the festival, I wandered through the display, marveling at the number and variety of cheeses that are made in this rural principality, which occupies just over 4,000 square miles in the north of Spain bordering the Cantabrian Sea. The largest cheesemaking region in Europe, Asturias has been called “the land of 40 cheeses,” but in reality, more than 300 cheeses are made here.

Four Asturian cheeses have received the EU’s coveted designation PDO (Protected Designation of Origin), which specifies that a cheese must be made in a particular place, using time-honored methods, and even details what the animals who supply the milk must be fed. These cheeses are Cabrales, perhaps the best-known of the five; Gamonéu (or Gamonedo); Casín; and Afuega’l Pitu. A fifth cheese, Beyos, is labeled PGI (Protected Geographical Indication), which is less stringent than PDO, but still attests that a product’s defining characteristics can be attributed to where it is made.

Asturias' geography is as varied as its cheeses. Home to Spain’s first national park, Picos de Europa, the principality boasts craggy, snow-capped mountains, wide sandy beaches, verdant valleys dotted with palm trees, and steep hillsides with limestone caves ideal for aging cheese. Its climate is mostly temperate. More than a third of this Paraíso Natural is protected from development, and its rural character underpins the region’s artisanal food production—especially when it comes to cheese.

A way to preserve excess milk

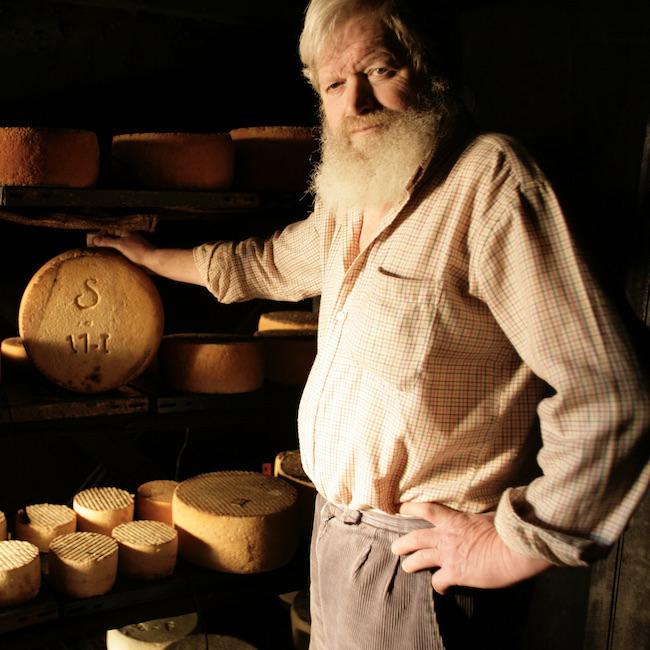

Just like in other parts of the world, for centuries cheesemaking in Asturias was a farmstead operation. Farmers who kept dairy animals made cheese as a way to preserve excess milk, and the cheese was consumed locally. “If people had animals they would sell them for meat, and if any were left in the spring and they had milk, they would make cheese,” says Marino González, who in the early 1980s (right about the time Asturias became an autonomous community) launched a cooperative of cheesemakers and a company dedicated to promoting Asturian cheeses as well as other products. “From town to town and area to area, people didn’t know about each other’s cheeses.”

While the history of the region dates back to the Roman conquests, the artisan cheese industry in Asturias is a modern development. Historically, cow’s milk cheeses were made in the valleys, while goat’s and sheep’s milk cheeses were made in the mountains, says González. Life was far more challenging in the mountains, and over time, many of the traditional goat, sheep, and mixed-milk cheeses disappeared. Today, some of these cheeses are being reproduced—and reimagined—by a new generation of cheesemakers, such as El Cabriteru, founded in 2016 by three generations of the Fernández family in the same region where Cabrales is produced. Together with his father and grandfather, Juanjo Fernández makes three raw milk blue cheeses: one with goat’s milk, one with sheep’s milk, and one with a mixture of the two (which one gold at the 2021 WCA). While the Fernándezes use traditional recipes, their blue cheeses are not as intense as the famously peppery Cabrales. Another example is Rey Silo, in Pravia, where master cheesemaker Ernesto Madera López produces two cheeses in the Afuega’l Pitu style—Blanco and Rojo (White and paprika-spiced Red), small, raw-milk domes that have the signature, slightly crumbly texture, but a softer and more rounded taste than their PDO counterparts (both won Silver at the 2021 WCA). In collaboration with chef (and Asturias native) José Andrés, Rey Silo has recently debuted a riff on Cabrales, named Azul Mamá Marisa for the chef’s mother. Encased in a dark, pebbly rind, its flavor as buttery and lush, with just a subtle hint of spice from the blue veining.

The cheeses of El Cabriteru are only sold in Spain, while the three Rey Silo cheeses are available in the U.S., as are all of the PDO cheeses. I suggest starting your Asturian cheese journey with them, and continuing it with a visit to Spain’s Paraiso Natural.

A in-depth look at the cheeses

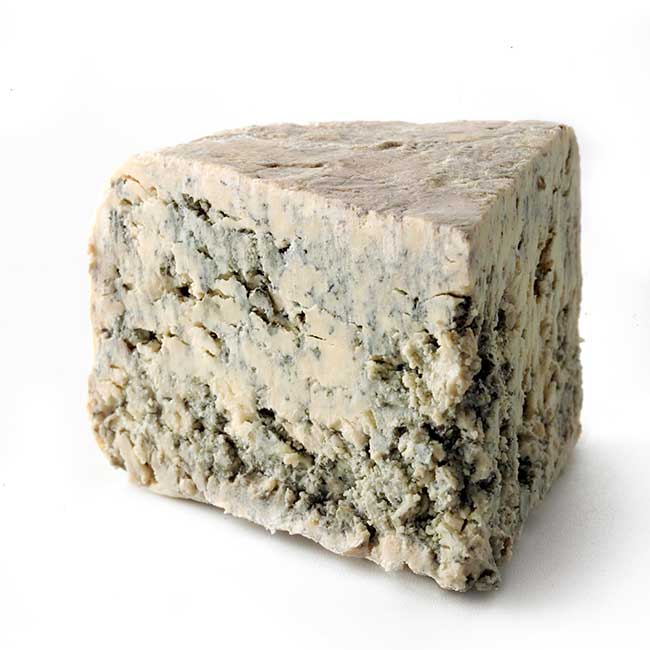

Cabrales PDO. Considered one of the world’s great blue cheeses, this intensely spicy and tangy blue was traditionally made with a mixture of milks and is now more commonly made with raw cow’s milk. The animals graze in high pastures in the warmer months, and the cheese is aged for 60 to 75 days in natural limestone caves where the mold that creates the characteristic blue veining, penicillium roqueforti, is present.

Gamonéu PDO. Gamonéu del Puerto is a seasonal cheese made in high mountain huts, while Gamonéu del Valle is made year-round in the valleys and is the variety most likely to be exported to the U.S. Made from 80 percent cow’s milk, 15 percent goat’s milk, and five percent sheep’s milk, the cheese is smoked before it is aged in natural caves for at least 60 days. Unlike many blues, it is not pierced, so any veining is just under the rind, rather than throughout the cheese. The flavor is earthy and rich with hints of smoke and spice.

Casín PDO. A firm, raw milk cheese that gets its name from the casina breed of cow native to Asturias, Casín has a high butterfat content and a smooth, uniform texture created by long kneading of the curds. Its barely discernable rind is hand-stamped with the mark of the cheesemaker. The flavor is pungent and strong.

Afuega’l Pitu PDO. A pasteurized cow’s milk cheese molded into a dome shape or a ball that resembles a small pumpkin, Afuega’l Pitu has a dense texture and a sharp, acidic flavor. It is made in two varieties—white and red—the latter has paprika added to the curds and can be quite spicy. The cheese is sold fresh, and is also aged from 15 to 30 days for the semi-cured and cured versions, respectively.