.png.transform/rendition-xs/image_image%20(1).png)

Sherry Cream: The Cream of the Crop

The world of Sherry is blessed by a variety of styles, yet none has done more to influence first impressions than Cream. In this article we’ll explore the rise, fall, and fragile rebirth of one of the world’s most misunderstood styles.

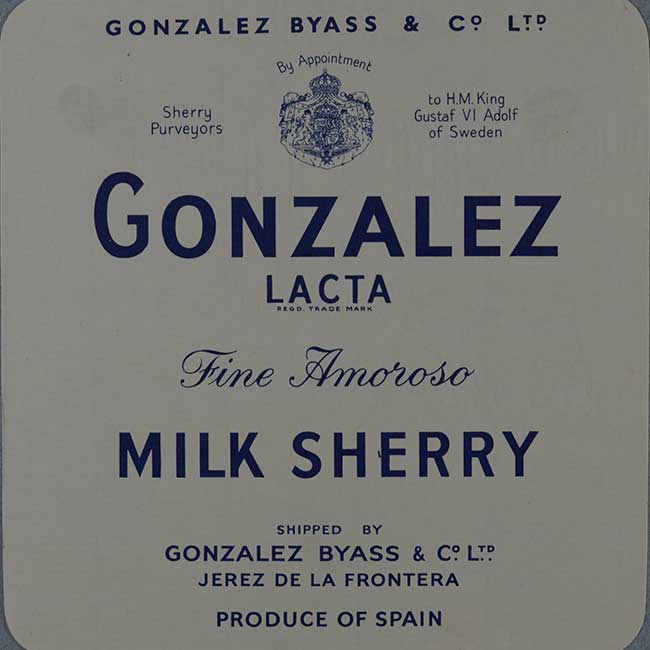

The story behind the birth of Cream Sherry is by now a famous one, mixing fact with an embellished bit of fiction. Let us start with Cream’s predecessor, the aptly named Milk Sherry. This popular style of sweetened Sherry dates back to at least 1634, later becoming closely associated with the historic wine merchants of Averys and Harveys, both based in the southwest English port of Bristol. These and other importers purchased wines from the Marco de Jerez and created proprietary blends tailored for a particular market. While “Milk Sherry” was commonly used for sweeter styles, it was one of many generic names, among which included Amoroso, Brown, Abocado, Medium, Rich, Golden, East India, and Dulce.

In the early 1880s however, Harveys of Bristol set out to create a richer, more refined blend of sweetened Sherry. We’re told that an aristocratic lady friend of the family visited their offices, and upon tasting their Bristol Milk, she was given a glass of the new blend, to which she responded, “If that was Milk, then this surely must be Cream.” Thus, Harvey’s Bristol Cream was born, going on to become the most famous Sherry brand of all time, selling as many as a million cases per year in the UK alone in the early 1970s. The style was so popular in fact, that practically all previous names of sweetened Sherry were replaced by Cream, with almost every Sherry merchant including the style in their portfolio.

So what went wrong?

The Sherry industry’s success post World War II, and that of Cream in particular, attracted many imitations in Europe and abroad, flooding the market with cheap copies that smeared the wine’s reputation. It wasn’t in fact until 1996 that Sherry became an officially protected name under EU law.

The damage was made worse by the breakneck speed at which the Sherry industry modernized during this time period, driven by large companies and their corporate approach to production. Efficiency and profits came to dominate, which coincided with problems of overproduction as demand started to decline. With consolidation, many superior quality vineyards and their resulting wines were blended into high-volume brands that competed on price.More than a few of these brands, regardless of style, were often “polished” before bottling with enough sweet Pedro Ximénez to cover up any rusticity and make them more consumer friendly. The result was that a generation of wine drinkers grew up assuming that all sherries were somewhat sweet by definition, with Cream the worst offender of all. As consumer tastes shifted towards dryer styles of wine during the last several decades of the century, the category of Cream was stigmatized by popular media and lumped together with other mass-produced, sweeter wine styles such as German Liebfraumilch and Portuguese rosé.

The patient comeback of quality Cream

What is unfair about the above comparison, is that unlike the latter two examples, Cream Sherry is indeed capable of outstanding quality, and in the right hands it can compete with the greatest sweet wines in the world for its balance, concentration, complexity, and length.

While sales of Cream have plummeted from their peak in the 1970s, today it is still the 2nd best-selling style overall after Manzanilla. Unlike Manzanilla however, which is overwhelmingly consumed inside the country, roughly 80% of Cream is sold abroad, mostly in the UK and the Netherlands. The bulk of this pertains to the BOB category of Buyer’s Own Brand, wines that are produced locally in the Marco de Jerez, but which are bottled under the name of a retailer, discounter, or distributor. Quality BOBs do indeed exist, yet the category is dominated by high-volume (often sweetened) blends that target the more commercial end of the market and which have seen the greatest drop in sales over the past decade.

While volume has fallen, value has remained steady and even increased in some instances, and these superior quality Creams are where the future lies. These wines are typically dominated by a blend of older Oloroso soleras, with selections of equally old Pedro Ximénez providing the sweetness. The amount of PX will vary by producer, but it often comprises 20 to 30% of the final blend, bringing sugar levels up to between 115 and 140 g/l.

The flavours and food pairing possibilities of Cream

Cream forms part of the oxidative family of sherries, and the best examples achieve an elegant harmony between the pungent flavours of Oloroso (roasted walnuts, dried apricot, caramel, toffee) and those of raisined PX (fig, dates, sultanas, and prunes). The best examples are indeed sweet, yet they are never cloying. While Cream is not known for its bracing acidity, balance is achieved through the intense savouriness of Oloroso and due to the fact that both wines, having spent many years in their own soleras, are blended together and transferred to a separate Cream solera where their flavours are allowed to integrate slowly over time. The ageing period can in fact last for decades, during which the wines gain in complexity and intensity due to the evaporation of water and the development of tertiary notes such as tobacco, leather, old wood, chocolate, cigar box, and roasted coffee grounds. Examples include Gonzalez Byass’s Matusalem Oloroso Dulce VORS, Valdespino’s Isabela Cream, La Bota de Viejo Cream by Equipo Navazos, Bodegas Tradición Cream VOS, and Lustau’s East India Solera Cream among others.

With some notable exceptions, the best Creams on the market are premium priced, as they very well should be. Many of these wines have been aged for an average of 20 to 30 years before bottling and even the most expensive examples offer tremendous value when compared to their still wine counterparts. This is especially true for Cream, whose star has been unjustly tarnished by the ubiquity of high-volume BOBs.

Regarding food pairings, marrying Cream Sherry with savoury dishes is certainly possible, but the wine is most at ease alongside dessert. For the overtly sensitive palates that scorn any wine which isn’t bone dry, it should be remembered that sugar in food decreases the perception of sweetness in wine. This helps explain why Creams are excellent partners for sweeter, more flavourful desserts, whose sugar levels would completely eradicate the fruit of dryer wines, stripping them of balance and leaving only alcohol, acid, and tannin. Something to keep in mind the next time you’re quick to form an opinion about Sherry’s most well-known style.