.png.transform/rendition-xs/image_image%20(1).png)

The Mediterranean Coast

This massive area includes much of present day Cataluña; there is a DO by that name as well that encompasses many of the top areas. These vineyard areas, whether near or far from the coast, share exposure to the warm winds of the Mediterranean. Many of the vineyards can be fairly moderate in climate and coastal, as in Alella, or remote and mountainous, as in Priorat. In Cataluña, elevation and proximity to the sea are crucial to understanding what is made there and why.

Alella offers some delicious whites from the Pansa Blanca grape (known as Xarel-lo in Cava country); it can be aromatic and expressive. White wines prosper in a number of sites along the Mediterranean, though not as frequently as the reds. Empordá makes some generous and textured Garnacha Blanca based wines, as do Montsant and Priorat. The Penedés region, home of 95% of the country’s Cava, is awash in white grapes: Parellada, Macabeo (or Viura) and Xarel-lo (or Pansa Blanca).

As throughout most of Spain, the greater number of prized wines are reds. DO’s such as Conca de Barbera, Costers del Segre, Empordá, Pla de Bages and Terra Alta have a dizzying array of wines from both international and indigenous grapes. Garnacha is far more planted than is Tempranillo; heat is a stronger factor in these regions and Garnacha a more forgiving grape. Syrah and the Bordeaux varieties show up in more elevated and protected sites.

The great success story in recent years is in and around the Tarragona region where some vines end up as Cava and some harbor red grapes. Priorat and its baby brother Montsant have unquestionably changed Spain’s wine landscape; these craggy hills and mountains allow Garnacha, Cariñena, along with small amounts of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Syrah to bake into powerful, heady wine, especially when coaxed from the old vines found throughout.

For some, Montsant is “poor man’s Priorat,” but that does a disservice to the area’s burgeoning reputation. Its elevations and terrains are not as extreme as Priorat, and Priorat’s famed licorella soils give way most often to limestone. But the quality/value ratios are absurdly stacked in the drinker’s favor.

The prices charged for some Priorat wines are as lofty as the stark pinnacles above these mountainous vineyards. Twenty years ago this entire area and its wines were nearly forgotten. In the early 1980s, a group of mavericks—René Barbier, Rioja’s Alvaro Palacios, Carlos Pastrana, Dafne Glorian, and José Luis Pérez—moved to Priorat. They created fantastic wines almost from the beginning, and they continue to improve the wines of the region.

The fame and pricing have attracted some to the region, but a quick buck is unlikely. As Alvaro Palacios of L’Ermita is quick to point out, the region itself is so difficult to work that only small amounts of very high-quality wine can be made. Anyone seeking to make wine through compromise will likely fail. The quality in Priorat, and the prices, shall remain high.

These wines are powerful and warm, if not occasionally hot, but they carry a fresh and even slightly racy core that gives them shape and complexity. The landscape too is distinct; the licorella soil mix of granite and slate adds a firmly mineral note that underpins every wine, regardless of the grapes.

Closer to the coast, Penedés is home to more than Cava, but sparkling wine is the 800-pound gorilla among the vines. The region is broken into the Alt-Penedés, Mitja-Penedés, and Baix-Penedés, reflecting the disparities in elevation within Penedés, with some vineyards planted in sites higher than 2,500 feet. All the grapes (especially the dominant three—Macabeo, Xarel-lo, and Parellada) at those altitudes can be intensely tart, akin to the raciness of Champagne.

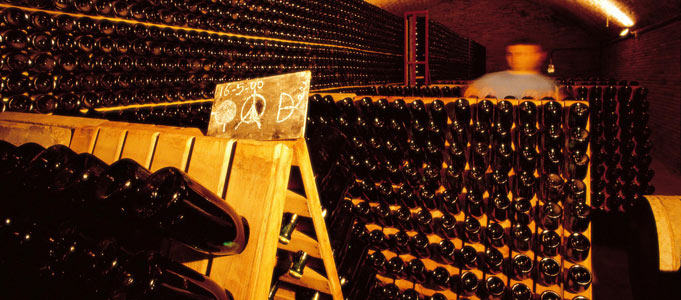

Many American consumers see Cava as limited to the wildly successful grocery-store brands. But there are complex and layered versions of Cava, as well as rich rosado styles to be discovered. Nine months of aging on the lees is required for standard Cava; Reservas must stay 18 months on the lees, and Gran Reservas require 30 months.

Farther southwest down the coast, the average temperatures go higher, and the opportunity to make light wines is baked away. Instead the Levante, an area around Valencia and Murcia, is wholly dependent upon water, and the grapevines suffer without it. Areas such as Alicante, Bullas, Utiel-Requena, Valencia and Yecla do good work where the producers are dedicated to quality, and where the vineyards are elevated enough to provide cooling nighttime temperatures.

One of the stars here is Jumilla, which is not so different from its neighbors except in its track record. The last two decades Jumilla has crafted delightful wines, whether from Monastrell (or Mourvèdre, as the French call it), Garnacha or blends with other grapes. But most wines are very reasonably priced and are often rich and delicious. The Bobal grape is exciting too but prospers more often in Utiel-Requena.

- Mediterraneo

- Mediterraneo

- Mediterraneo

- Mediterraneo

- Mediterraneo

- Mediterraneo

- Mediterraneo

- Mediterraneo

- Mediterraneo

- Mediterraneo

- Mediterraneo